Sports Reference Blog

The Real Problem with Baseball’s Defensive Stats

Posted by sean on September 8, 2014

After reading Jeff Passan's article about WAR and his view of its failings, I got a little hot under the collar and intemperate in my discussion of the issue on twitter.

The defensive metrics are constantly critiqued. I agree that there may be issues with the defensive stats, but my issues aren't the ones brought up by the critics. I believe that the metrics do a decent job of measuring the percent of time a particular ball with a particular hang time has been caught in the past. All you need for that is a stopwatch and a way to mark the play's location on the field. Sure there may be biases in this, but there are biases in who batters and pitchers face or even what umpire they appear against. So this isn't the biggest issue with fielding stats.

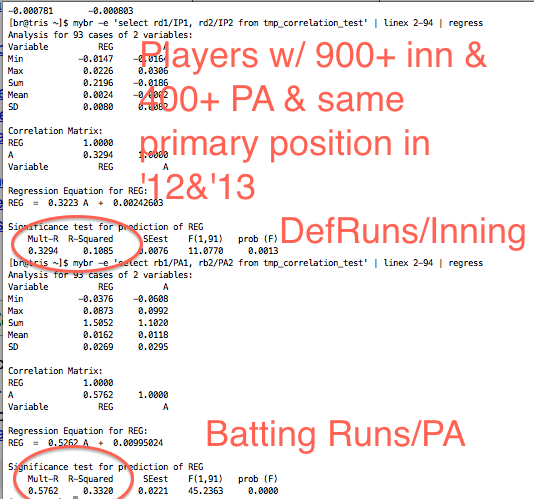

It's also true that fielding stats don't correlate quite as strongly year to year as the batting stats do (see chart after break), but there is also a lot more variability in opportunity for fielders than for batters (and more variability in batting stats than people perceive). A batter is going to get 3-6 PA's per game every game. The distribution of balls hit to fielders is much more random. But even this isn't the big issue with fielding stats.

(Chart of 2012 to 2013 correlation of defensive and offensive runs for near full-timers who didn't change primary position.)

The main issue with defensive stats is how do we account for positioning versus fielding skill.

For example, our defensive numbers come from Baseball Info Solutions and for every ball put into play BIS looks at where the ball is caught and its hang time and compares it to similar plays from previous (or even future games as it's updated at year end also) to know that 12% of balls like this were caught over X-number of years. Which is pretty straightforward to do and is probably what most everybody would do if they wanted to analytically measure fielding value.

The issue with defensive stats, however, is this. If the team is really good/bad or even lucky/unlucky at positioning players, it may be that the 12% catch would actually be caught 70% of the time given the player's initial positioning. BIS doesn't track player initial locations (other than noting shifts) because they aren't available on TV and even if they did, which number should we go with (88% or 30%) as we don't really know how much of the positioning is due to the team or the player?

Now if we just look at location and hang time the fielder making the play saved 88% of a hit, but we could also make the case that the fielder saved 30% and the team saved 58%. Do the fielding coach/aGM/scouts need a WAR number? The fact is some portion of a hit was prevented and we try to recognize that value.

There are other strategic impacts all over the field (platooning is a similar case).

This is something I've been thinking about a lot lately in the hope that we'll see detailed positioning from MLB's new system. I'm not sure there is a satisfying answer here. Somebody earned that 58%. One approach describes what actually happened on the field and gives the value to people on the field and another describes the player's skill in fielding.

This is also why BIS throws out shift plays. These non-standard fielder locations lead to very large runs saved values since there are plays made that would be impossible to make without being in a shift.

My main point here is to caution people that even if we had perfect fielder location data, we would not then immediately have a completely satisfying answer as to which fielder was the best.

If you want to read more about WAR, we explain most all of it in the about section on baseball-reference.com.

Maybe we need something like Defensive Runs Above Team, and establish a "teams runs saved" and only credit players with the benefit they provide above that.

Of course, how do you tell what's the base amount of runs saved for the team, because those numbers are calculated with the player you're supposed to be isolating. and no two teams shift exactly the same based on who's on base, and who's fielding the other positions.

I'd say positioning is a defensive skill.

I'd like to see a system that distributed credit to all the fielders based on team plays made and not made with less emphasis on which fielders made the play. Why, no, I haven't thought this system through.

How does BIS decide what constitutes a shift?

Let's say there's a lefty batter at the plate. As long as my shortstop doesn't move to the right hand side of second, is it then not a shift?

It is my view that all that is required is range factor with a couple of common sense adjustments, because, as is suggested above, positioning is a defensive skill. The adjustments are for team quality, pitching strike outs, ball park effects (lots of foul ground pop outs in Oakland) and a balls to infield - balls to outfield adjustment. See (slightly) more details at http://statsguyma.blogspot.com/2014/08/adjusted-range-factor-who-was-most.html

One thing I never understood is how in the world is this info available for, say, Babe Ruth? There's no way there's enough available to determine what his defensive WAR should be, yet he has one for every year he played.

Even crazier is 19th century players with defensive WAR stats.

Rich,

For Babe Ruth it's largely based on things like chances, assists, team staff handedness, etc.

For fielding stats, the rating should be based on a combination of many systems, not just one. Weight them by available data, how well the method adds up to get the whole team's rating versus evaluating the team as a unit, year-to-year correlation. Use DRS, TZ, UZR (if you have it), WOWY, the traditional stats (which should be calibrated for modern data to fit them to the PBP systems).

I don't think you can assign blame to a particular fielder for every hit. Some things are just hits. Plus, if a player gets a lot of balls hit his way due to the type of pitchers he has, that's going to make his stats look better no matter how you calculate it. Oakland's third baseman, Donaldson, for example, has a really high "range factor," (chances per inning) and he's also leading the league in errors. I've never watched him regularly, but the fact that he's a converted catcher leads me to believe he's probably not Brooks Robinson. Still, he has a high "defensive WAR," and a high rating in all the sabermetric fielding stats due to the high range factor.

Also, I know they have a stat called defensive efficiency which measures what percent of balls are fielded by a team that land in play. It's a pretty interesting stat. But still, if one team's pitchers are giving up line drive rockets, they will probably have a lower defensive efficiency than a team whose pitchers are giving up weak popups or grounders.

Well, no, the main problem with defensive stats is we can't even get the defensive stat people to agree on things. They diverge on who is a average fielder verses a great fielder. When 2 different WAR systems have 2 totally different defensive values for players, that's the problem with defensive stats.

Doesn't Win Shares work backwards from the team to the individual? The defensive component of Win Shares might not be that useful inandof itself, but maybe the concept is sound. A team's defense functions as a unit, with contributions from all of the fielders and the coaches (plus the pitchers of course), so maybe it's better to start with defensive efficiency or some other team stat and work backwards to get the individuals' contributions.

I'm not sure that I would consider positioning to be a fielding skill, especially in today's game...at least not a physical skill. Doesn't it come from massive data collection? Some players will be better at assimilating and employing this data than others but you still will have instances where the manager or a coach will gesture to a player to get him to change his positioning as was done in the old days of the game.

I've long thought that if someone plotted the steps a middle infielder took to get to a ball, one would have a "bell curve" showing his range. A tall, narrow curve would indicate good positioning while a flat, broad one would probably be indicative of poorer positioning. Similarly, a long left or right tail could be indicative of better range in that direction, especially if the overall curve tended to be tall. Now that Field f/x data is on the threshhold, this type of analysis might be possible.

I've long maintained that a significant element of defensive value comes from positioning, which isn't necessarily a defensive player's individual skill. So, on that point, I agree with you. In addition, defense is treated as zero game. What about plays where two or even three fielders can record an out. Why aren't all three credited? When you add up these issues along with the other more commonly cited limitations mentioned above, it exposes significant flaws in the whole concept of defensive metrics that too many with a stake in them are quick to dismiss. For that reason, I think WAR is increasingly become a marginalized statistic, and am shifting back toward a deconstructed evaluation of players. Let the offense statistics serve as one leg and a variety of defense analyses be the other. That seems to make more sense than continuing to try to cram everything into a catchall like WAR.

William says #12: What about plays where two or even three fielders can record an out. Why aren't all three credited?

That's a good point. I've been keeping score in baseball games for a long, long time and it was just a few years ago that I decided there was such a thing as an outfield pop-up. I would always score it as a fly ball but if an infielder made the play I would have scored it as a pop-up. So if if infielders and an outfielder all could have made the catch it goes as a pop-up for the OF, too, nowadays.

Another thing I have been thinking about quite recently is scoring two assists on a play for one player who bobbles a ball, then completes the play. I'd see that and jokingly say, "4-4-3." While the rules only allow one assist for the player, this type of scoring shows better what happened.

#12 , on these discretionary plays, these are plays where the avg fielder makes the play practically 100% of the time, so if Jeter catches a popup between short and third he gets 100% of the credit for making a play that is made 100% of the time. This actually would have zero impact on his rating since he did exactly what an avg fielder would do and our ratings are relative to avg.

So super easy or discretionary plays have almost zero impact on the rating, so this is a flaw with the chances based metrics, but not a flaw with defensive runs saved.

[…] he wasn’t incorrect with some of the points he made about WAR. I, along with Dave Cameron, Sean Forman, and many others, disagree with various points he made in what was ultimately a well-meaning and […]

The main problem with WAR isn't defensive WAR. It's doing what it should, given the information we have. No, the main problem with WAR is that dWAR and oWAR aren't on the same scale; and that's a problem with oWAR.

Other than baserunning effects, the hitter is done creating wins when he puts the ball in play. The fielder starts creating wins at the moment the ball is put in play. dWAR considers it precisely that way: the fielder is credited for the outcome he produced, relative to the expected outcome given the particular BIP (hit to a particular location, with a particular hang time). If he records an out on a BIP that likely would have produced a double, he gets more credit than if he records an out on a BIP that is routinely converted to an out. dWAR credits the fielder for what the fielder did, controlled for the opportunity created for him by the hitter.

oWAR considers it based on the outcome of the BIP, not the BIP itself. If a BIP has an expected outcome of +0.6 runs, and the fielder makes a spectacular play that converts it to an out at -0.3 runs, the fielder gets +0.9 runs, the hitter gets -0.3 runs. If instead on that BIP the fielder failed to make the spectacular play, maybe the outcome is +0.7 runs. In that case the fielder gets -0.1 runs (the defense is -0.1 run worse off than expected given the BIP) and the hitter gets +0.7 runs.

Note that the swing in what the hitter gets credit for is a full run (+0.7 vs. -0.3), and has nothing to do with the hitter's actions. In both cases the hitter created a +0.6 run BIP. But that's not what is credited in oWAR. oWAR credits the hitter for what the fielder did.

Does this mean oWAR is inaccurate? Yes and no. oWAR as a hitter ranking tool is still working fine. For it not to work in that capacity, a hitter would have to be subjected to so many more web gems than other hitters. I doubt that is the case, although I think every hitter probably feels like it happens to him.

The problem only comes when combining with dWAR, because oWAR and dWAR are effectively on different scales. It is the combination of the two that has people flipping out, and it's natural to be suspicious of dWAR if WAR looks off and you're already comfy with oWAR. The general wisdom is dWAR needs to be scaled back to be comparable with oWAR, which is functionally equivalent to scaling up oWAR.

The issue I raise with oWAR indeed suggests that oWAR is understated. When BIP are fielded as expected, both oWAR and dWAR are fairly accurate. When they aren't fielded as expected, we have two scenarios. Either we have a likely hit turned into an out, in which case the value created by the BIP is greater than the value attributed to the hitter in oWAR. Or we have a likely out turned into a hit, in which case the official scorer notes it as an error, and the hitter's "credit" for an error is in line with the BIP value. In both these cases dWAR gets it right, but only for the latter is oWAR giving proper treatment. Thus the only case where oWAR will systematically and materially misestimate the value produced by the hitter on a BIP is when the fielder robs the hitter. And in that case, the misestimation is an underestimation.

(The above simplifies things. In reality on every BIP there will be differences between what the hitter does and what he gets credit for. But the material differences are on the likely hits converted to outs, the great defensive plays.)

When we combine oWAR and dWAR, we're giving in dWAR a credit for taking away value from the hitter that oWAR doesn't credit to the hitter. That makes the stats improper to combine.

If all oWAR did was to replace what it does on BIP now with the BIP expectations already used in dWAR, they would be on the same scale. Or, if we recast dWAR to focus on outcomes only (like oWAR) rather than control for the BIP type and location, they would be on the same scale. But in the latter we would lose a lot of the signal on dWAR. This is why I say the problem is with oWAR.

[14] That makes sense, but what about the other players who could have made the play? For them, it wouldn't have been routine effort.

Here's an example:

1. An easy fly ball is caught by the CF, but the LF ranged over and also could have made the play. He gets no credit, but this effort demonstrates an ability to make extraordinary plays in the event they are needed.

2. The same fly ball is caught by another CF, but this time, the LF does not have the range to also make the play. He also gets no credit, but because a LF with range also isn't rewarded, he looks just as good relatively speaking.

There's a more practical example as well. I've watched just about every inning of every Yankee game and have seen Brett Gardner range into CF on many occasions, effectively "stealing" balls from Ellsbury. Is that why Ellsbury's defensive metrics are down this year? If so, it would be an example of how zero sum distorts the total, especially if it combines with a team's positioning philosophy (maybe Yankees shade Ellsbury toward right to cover Beltran, and that leads to a net decrease in balls caught) to skew the relative numbers.

William,

We aren't looking at the player's innate ability to catch balls. We are assessing the value of what happened on the field. If Ellsbury caught fewer balls, he caught fewer balls. The fact that Gardner poaches some of his balls means that Ellsbury's numbers may not be as large in magnitude, but I don't see how it would change whether he is above or below average on the balls he's assigned.

Likewise for pitchers or hitters, we would likely look at LD rate or FIP if we were concerned about ability. A hitter with 20 at'em balls and slightly worse resulting stats is likely a better hitter than a batter with 0 at'em balls. If I'm a team looking at free agents or trade targets, I look at that number.

If we (as we focus on) want to know why the Orioles are in first and the Yankees aren't, I think that the focus on the value of what actually happened (rather than what happens on average) is far more applicable.

I never said DRS was perfect or couldn't be improved, but I do think it's much more informative than not.

[18] I know what's being done, but measuring defense based only on what happened on the field is flawed. Unlike offense, in which we can isolate the contributor, even if the outcome is deemed to be luck, on defense, there are nine men working to create one outcome: an out. I agree that outcomes tell us why the Orioles are better than the Yankees, but that's a team assessment (relative range of other fielders, pitchers ability to hit location, positioning of team, etc.), not necessarily one of individuals.

DRS is "more informative than not", but so too are scouting reports and crowd sourcing. All are relevant to assessing defense. However, when we try to cram offensive and defensive evaluations into one metric, both become distorted.

[…] the defensive component of WAR into question. Predictably, this was met negatively with both Baseball Reference and Fangraphs responding […]